Los Angeles Times Sunday February 11, 1996

COPYRIGHT (c) 1996 Times Mirror Company

Rocketdyne Razing Historic Testing Stand

By MACK REED, TIMES STAFF WRITER

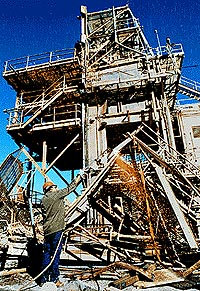

White-hot acetylene torches bite into the steel bones of the abandoned hulk known as Vertical Test Stand-1, cutting apart the rusted cradle of American rocketry.

White-hot acetylene torches bite into the steel bones of the abandoned hulk known as Vertical Test Stand-1, cutting apart the rusted cradle of American rocketry.

Rocketdyne has chosen to demolish this relic of the Cold War and the space race. Not because it cares little for history, but because it needs to save money.

U.S. scientists of the ’50s and ’60s labored feverishly here at Rocketdyne’s rugged Santa Susana Field Laboratory, testing prototype rocket engines that they prayed could beat the Soviets.

Here, they breathed fire into the dreams of Mercury, Gemini and Apollo, and designed forerunners of the massive booster engines that still fling the space shuttle into orbit.

But on Feb. 2, demolition workers began toppling the historic five-story rack of thick steel and scarred concrete in a clanging shower of scrap. Coming months will see them dismantle two more stands, where scientists developed the powerful Saturn rocket engines that lifted astronauts to the moon.

But on Feb. 2, demolition workers began toppling the historic five-story rack of thick steel and scarred concrete in a clanging shower of scrap. Coming months will see them dismantle two more stands, where scientists developed the powerful Saturn rocket engines that lifted astronauts to the moon.

Fact is, Rocketdyne says it plans to save $30 million a year in upkeep on these–and 172 other obsolete test stands, pillboxes and storage sheds at its 2,700-acre Santa Susana Field Lab in southeastern Ventura County–by demolishing them.

The metal will go to the scrap yard, and the craggy open-air test arenas will be abandoned to the crows and coyotes.

Some engineers shrug, scientific and practical.

Obsolete gear is too costly to keep, they say, and it stands in the way of progress. It was only a matter of time–and dollars–before all this had to go.

Yet for many Rocketdyne old-timers, the demolition of historic VTS-1 cuts deep.

“It’s kind of a monument that’s come and gone,” says veteran engineer Bill Vietinghoff. “And no one except those few who’ve worked here will realize it.

“It’s not as well-known as something like, say, the Queen Mary or the Brooklyn Bridge,” says Vietinghoff, 68, who cut his teeth on VTS-1, testing the nation’s first primitive liquid-fuel rockets. “But it was a prideful thing in its day. It was a symbol of progress, power and technology.”

In the late 1940s, North American Aviation of Long Beach took over a set of rocky amphitheaters in the Santa Susana Mountains. Where once Tom Mix filmed silent westerns, now America would build its first rockets.

North American needed a stable, reusable structure where it could lower a rocket engine into place, bolt it down, fuel it, ignite its powerful, booming flame and watch how it worked from a nearby blockhouse without having the rocket fly off out of control.

So, engineers modeled the towering VTS-1 after wartime Germany’s rocket lab at Peenemunde. They installed a water-cooled steel “flame-bucket” beneath it to catch the downward thrust. They borrowed a liquid-fuel engine design from the Nazis’ deadly V-2 buzz bomb–along with some of the Germans who designed it.

So, engineers modeled the towering VTS-1 after wartime Germany’s rocket lab at Peenemunde. They installed a water-cooled steel “flame-bucket” beneath it to catch the downward thrust. They borrowed a liquid-fuel engine design from the Nazis’ deadly V-2 buzz bomb–along with some of the Germans who designed it.

And in test after test on VTS-1, they set about refining the science of rocketry.

Before long, the U.S. government saw the strategic power in rockets that could carry weapons into the upper atmosphere. The fledgling lab was pressed into military duty.

The military pumped in money and manpower, hammering Rocketdyne into one of the vital foundries the nation needed to forge the weapons of cold war.

Rocketdyne’s ranks swelled with young, idealistic scientists who found Flash Gordon thrills in the cutting-edge realm of rocketry, and patriotic pride in strengthening Uncle Sam.

“We were just a new bunch of kids, fresh out of the service, anxious to get a hold on the world,” said former instrumentation engineer Clement Cecka, 71, who moved out to Rocketdyne in 1950 from Minneapolis to join his brother. “The camaraderie was unbelievable.”

Ex-Marine Ernie Barrett had come a year earlier from North American’s Long Beach headquarters, where he was working on the prototype B-45 jet bomber.

“We worked well together,” recalled Barrett, now in his 60s and retired to Canoga Park from 43 years as a test engineer and supervisor. “Everybody was very excited about what we were doing.”

In its heyday, the rocky lab perched midway between the San Fernando and Simi Valleys was a tense, heady place.

In its heyday, the rocky lab perched midway between the San Fernando and Simi Valleys was a tense, heady place.

Engineers worked seven days a week and two shifts a day, sometimes three.

Guys like Bill Vietinghoff sweated the design details, tweaking bastardized V2 engines into new prototypes at first, then standing on Germany’s shoulders to reach even higher for new rocket designs with longer range and stronger thrust.

Guys like Ernie Barrett did the grueling test work, overseeing two, three, five firings a day. Barrett watched mechanics lower a new engine onto VTS-1 by crane and hook up the latest experimental rocket juice. Then he gave the orders to light it up.

As high-speed cameras whined to life at 3,000 frames per second, and the engines vomited gouts of flame into a water-cooled steel pit below, guys like Clem Cecka measured the burn, the fuel flow, the vibration and heat.

When the very first rocket was fired sideways from the Horizontal Test Stand that was bolted onto VTS-1 in 1952, Cecka was working the night shift.

The test team was doubtful, tense, he recalled: “They didn’t know if the fuels would ignite and flow properly in that position.”

Then came the blast of a perfect test: “It just blossomed out with a plume of fire probably 30, 40 feet long, just a long finger of fire straight out in the air,” he said. “The roar was just indescribable. Of course, we were in a blockhouse, but even then, the roar was deafening.”

Then came the blast of a perfect test: “It just blossomed out with a plume of fire probably 30, 40 feet long, just a long finger of fire straight out in the air,” he said. “The roar was just indescribable. Of course, we were in a blockhouse, but even then, the roar was deafening.”

Whether engines fired successfully, shut down early or blew up on the stand, the scientists learned.

They pored over readouts for mistakes and clues. Then they shipped the engines back down the twisting road to the Rocketdyne plant in Canoga Park for analysis and rebuilding, and tried again.

Would another fuel burn hotter? Stronger? What if we tighten this valve or reshape that thrust chamber, add another pump? Can we beat the Russians? Can we win?

They tried weird, exotic fuels–ethyl alcohol, fluorine, liquid oxygen chilled to 298 degrees below zero.

They monkeyed with the basic design: pumping fuel through tubes sandwiched inside the walls of the thrust chamber to help cool the engine, or designing side-thrust jets to give missiles a football-like spin.

They relied on primitive test gear–slide rules for complex calculations, vibration monitors and oscilloscopes cannibalized from oil-drilling companies, scratch-built gauges tough enough to measure horrifically strong flame and fuel-flow and thrust. “Pushing the state of the art,” they called it.

They relied on primitive test gear–slide rules for complex calculations, vibration monitors and oscilloscopes cannibalized from oil-drilling companies, scratch-built gauges tough enough to measure horrifically strong flame and fuel-flow and thrust. “Pushing the state of the art,” they called it.

“We had to develop our own valves and pressure regulators; there wasn’t anything commercially being built at all,” Barrett recalls. “Where are you going to find a store that would handle liquid oxygen, or a valve that could handle 5,000 psi that you could hold in your hand?”

But when it all worked, when test-firings stretched from tense milliseconds to roaring minutes, the rocket men knew they had crossed into uncharted space.

For Cecka, the turning point came in 1950, the first successful test of the Redstone rocket–a V-2 offspring that carried America’s earliest nuclear warheads and later blasted Mercury astronaut Alan Shepard off for the first American manned rocket flight in 1961.

“We knew we could do anything after we got that first one done,” Cecka said. “You get that feeling that there’s nothing we can’t do anymore, that eventually we could solve any problem.”

In the mid-1950s, spies brought word of new, increasingly powerful Soviet missiles, and the United States ratcheted up the pace of testing at Rocketdyne.

A dozen new test stands were built in 1956. Engineers pulled even longer shifts. More were hired on.

Scientists stuck their heads up inside barely-cool nozzles for inspection, then yanked the rockets off the stands and bolted new ones on for the next test.

As engineers tried to squeeze more punch out of the rockets, recalls former instrumentation engineer Ed Mosbrook, “The Atlas engines were just blowing up right and left.”

Recalls Barrett, “It was a race to be Number 1. . . . If they’re going to launch something, we’d better have something to launch back.”

They developed engines for short- and intermediate-range missiles like the Redstone and Thor rockets. They perfected engines for early intercontinental ballistic missiles and cruise missiles such as the Navaho.

They developed engines for short- and intermediate-range missiles like the Redstone and Thor rockets. They perfected engines for early intercontinental ballistic missiles and cruise missiles such as the Navaho.

Then, abruptly, Rocketdyne’s main mission changed.

Liquid rockets proved too slow to launch and hard to maintain for the split-second pace of nuclear war–all that fussing with supercooled fuels like liquid hydrogen and oxygen.

The military turned its attention to other contractors who built more stable, faster-launching solid-fuel rockets.

And as the 1957 launch of the Russian satellite Sputnik threw a new shadow over America, Mosbrook recalled, Rocketdyne turned its attention toward beating the Soviets in space.

“I think a lot of us were a lot happier when the space program came along,” said Mosbrook, 59, who worked on through the ’70s and ’80s to help perfect the massive space shuttle booster engines before retiring in June. “You were doing things for science and not with the intention of mass annihilation.”

But the pace was just as manic.

At its height in 1964, Rocketdyne had 9,000 people working on “the hill” and more at the Canoga Park plant, chasing the late President Kennedy’s mandate to put a man on the moon.

Now they were testing engines with massive power–1.5 million pounds of thrust for each of the five engines in Apollo’s Saturn booster.

Cecka remembers focusing on the other end of the Apollo vehicle–a little 3,000-pound-thrust engine no bigger than a garbage can that had to lift the Lunar Excursion Module off the moon so the astronauts could come home to Earth.

“When the guys landed on the moon [on July 20, 1969], nobody knew if that thing was going to work and they’d get off again,” he said. “I spent many hours overtime up at the lab, getting that thing perfected on Sundays and whatever. And when they pushed the button to get off the moon, boy, it worked perfectly. That had to be the high point of my life, knowing that those guys were safe and sound and on their way.”

The stress was intense.

“We worked hard, and we played hard,” said Mosbrook.

Friday nights meant drinking bouts at the Wooden Shoe, a Roscoe Boulevard eatery that boasted the best barbecue beef sandwiches in the San Fernando Valley. Some guys got “flat-ass drunk,” Mosbrook recalled.

“We used to have parties down there for whatever occasion,” said Barrett. “A hundred runs, 50 runs, someone’s promotion–we’d walk out of there and there’d be a quarter-inch of beer on the floor.”

Some indulged in stress-venting pranks at the field lab involving local wildlife, Vietinghoff recalled: Drop a snake into a vat of subzero liquid nitrogen, then fish out the hard-frozen serpent and dump it into someone’s lunch bucket.

“Or they’d catch tarantulas and mount them on their helmets,” he said. “They’d spray them with Krylon spray, which was very attractive.”

But all the engineers recall they worked around VTS-1 and the other sites with grim determination and chest-swelling pride that they were boosting America into the rocket age.

“That test stand started the evolution of rocketry,” said Barrett.

“We were first,” he said. “How are you going to hire anybody out of school with this kind of experience? It’s like the first car that Ford ever built: From there evolved all kinds of cars. And this was where we learned to run engines and design them.”

For Barrett, preserving VTS-1 would mean little to outsiders. “I’ve got my memories,” he said. “I know the people.” But the demolition saddens Cecka.

“That should never have happened,” he said. “That was the stand that started the whole thing, and it should have been left as a historical monument. I put a lot of time in on that stand.”

Rocketdyne still fires engines on some of the old Cold War stands. The rumble of Atlas and Delta rockets for satellite missions often booms down from the hill.

But the rest are bound for the scrap heap–save for a few small chunks of rusted VTS-1 girders coated with peeling yellow paint that will be “prettied up” as souvenirs for some Rocketdyne workers, said special projects manager Jerry Gaylord.

The test stands that clamped roaring Saturn J-2 rocket engines firmly in place through 1975 are also marked for demolition.

The cost of upkeep and insurance on the unused stands is too high, said Gaylord. “We no longer need them.”

For Mosbrook, the rocket lab remains a place of almost mythic power.

His firmest memories carry the scary rattle of volatile liquid oxygen bubbling through fuel-loading pipes, the tense blockhouse chatter of countdown, the smoke and fire and boom of rocket engines that belched a monstrous flame “right on the ragged edge of explosion.”

He wants to go back to the lab with some of his old colleagues and record their memories on videotape before it is all gone. Says Mosbrook, “Those were some of the best years of my life.”